Lesson 6: Relative Pronouns & More

Infinitives

If you have ever learned about infinitives before, the first thing you probably think about is a "to-infinitive”: “to be,” “to go,” “to jump,” and so forth. The “to-infinitive” is also called the full infinitive. The full infinitive is usually made by taking the first-person singular form of a verb and adding “to” to the front of it (e.g. “I go” -> “to go”). We label infinitives Inf when parsing, no matter how they are being used in the sentence.

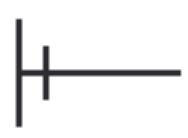

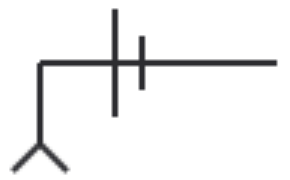

This is the Infinitive Shelf. While infinitives are verbal nouns, they often function as adverbs or adjectives as discussed in the previous step. So the way that the infinitive shelf attaches to your sentence will vary.

Full infinitives can be used adverbially to show purpose.

When used this way, the infinitive is functioning as an adverb, telling us more about the main verb. The purpose of taking the course is “to learn.” Notice that it would be natural to add an “in order” in front of an infinitive of purpose. “I am taking this course in order to learn grammar.” Notice also that the word “grammar” is the direct object of the infinitive “to learn.” As mentioned before, non-finite verbs, though acting like a different part of speech, still have some verb aspects…like having direct objects!

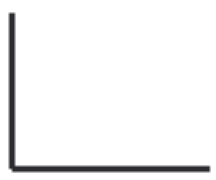

Since the infinitive label stays the same no matter what part of speech the infinitive is acting like, the label does not tell us what the infinitive is doing in the sentence. Our diagrams, however, will show both that it is an infinitive and its role in the sentence. For our adverbial full infinitive above, we need another shelf in addition to the infinitive shelf.

This is the Verbal Modifier Shelf. Infinitives (and participles, as we will see later) that are acting either adverbially or adjectivally are attached to this shelf. Incidentally, this is the last shelf you will be learning for this course!

Notice that the verbal modifier shelf attaches below the verb, and the infinitive shelf is attached to the verbal modifier shelf. Thus we can see both that we have an infinitive and that it is acting as an adverb.

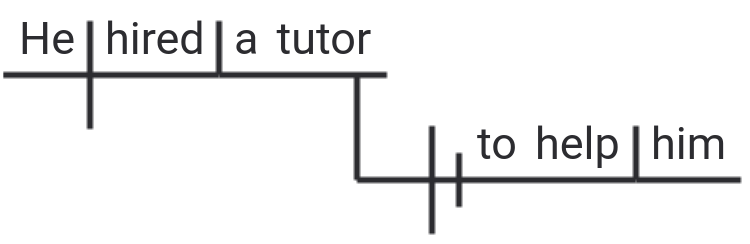

Full infinitives can be used adjectivally to modify nouns.

Even though the structure of the above sentence is similar to that of the first sentence, here the infinitive “to help” is acting like an adjective and modifying the noun “tutor.” Notice that the same verbal modifier shelf is used, but it is placed under the noun “tutor” to show what it is modifying and showing that it is adjectival.

This can be a difficult distinction to make! How can you tell if the infinitive is acting adverbially or adjectivally? Look for the borrowed subject of the infinitive. In this sentence, the direct object, “tutor,” is the subject of our infinitive “to help.” The tutor is the one helping. The other possible subject would be the subject pronoun “he.” Is “he” helping? No, “he” is hiring the tutor to get help. So the subject of “to help” is the “tutor,” and therefore the infinitive is modifying the noun “tutor” and acting adjectivally.

Full infinitives can be used adverbially after a predicate adjective to give more information.

When a full infinitive is added after a predicate adjective, the infinitive is always modifying that PA, and therefore is always acting adverbially.

Full infinitives can stand substantively as the subject or object of a sentence.

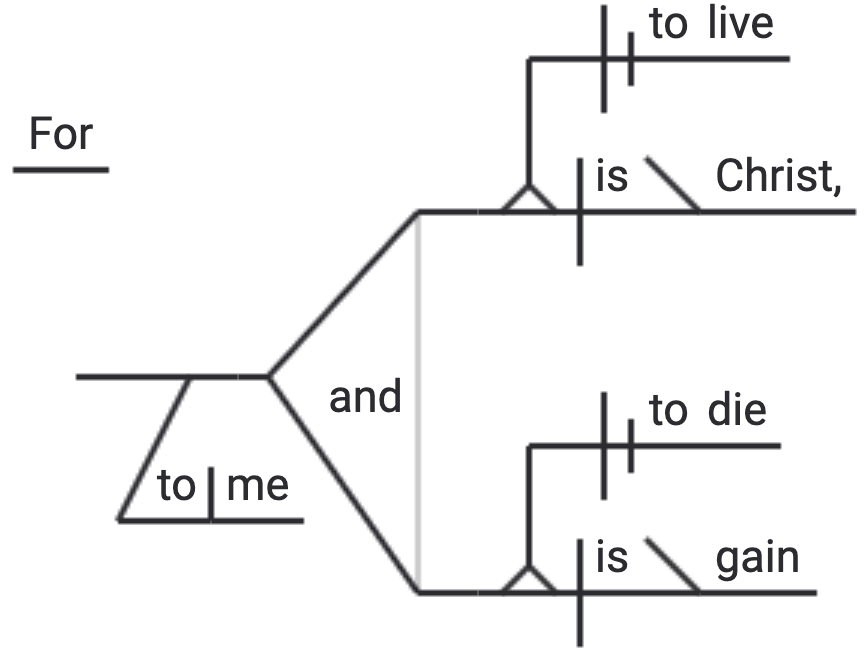

In this verse from Philippians, we have two clauses combined with the coordinating conjunction “and.” Neither of the clauses in the sentence has a regular noun or pronoun for its subject, but rather, they have a full infinitive as a substantival subject. Both of the linking verbs are followed by predicate nouns, which are (figuratively) renaming the infinitive subjects.

To diagram an infinitive as a substantival, use the substantival shelf with the infinitive shelf attached to it.

In the above diagram of Philippians 1:21, you can see that where the subject would be for each of the two clauses, a substantival shelf is attached, with the infinitive shelf attached to it.

Note that when an infinitive is acting as a subject, it doesn’t grammatically have any subject of its own (borrowed or otherwise). “To live” and “to die” here are presented simply as concepts.

Bare infinitives

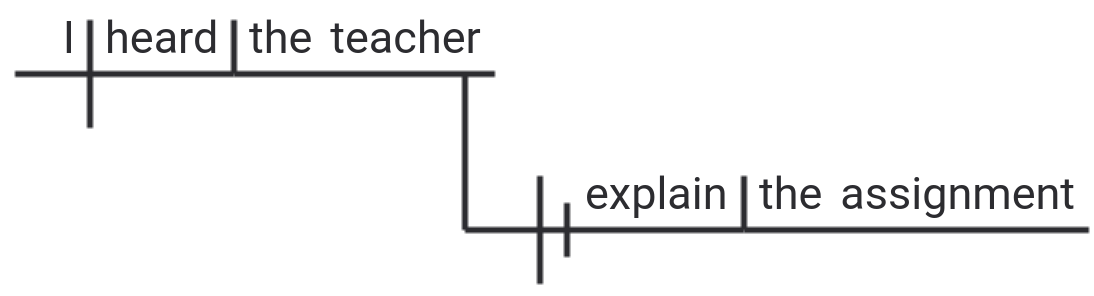

When paired with a sensory verb (“to hear,” “to see,” etc), the infinitive drops the “to,” but functions adjectivally in exactly the same way as our example above. The trick with these types of sentences is not difficulty in parsing or diagramming them, but rather in recognizing what you are looking at. Understanding that you are looking at a bare infinitive might be more a process of elimination of the other options, rather than seeing what it is straight away.

Parse and diagram these exactly as you would a full infinitive acting adjectivally.