Lesson 10 | Cantillation

[2] Ketiv and Qere

When you read the Hebrew Bible on Biblearc, you will occasionally notice words without vowels, as with one word in Psalm 100:3 below. Do you see it?

Why are there no vowels under that one word? To answer, we need to talk about the preservation of the Hebrew text.

An Ancient Oral Tradition

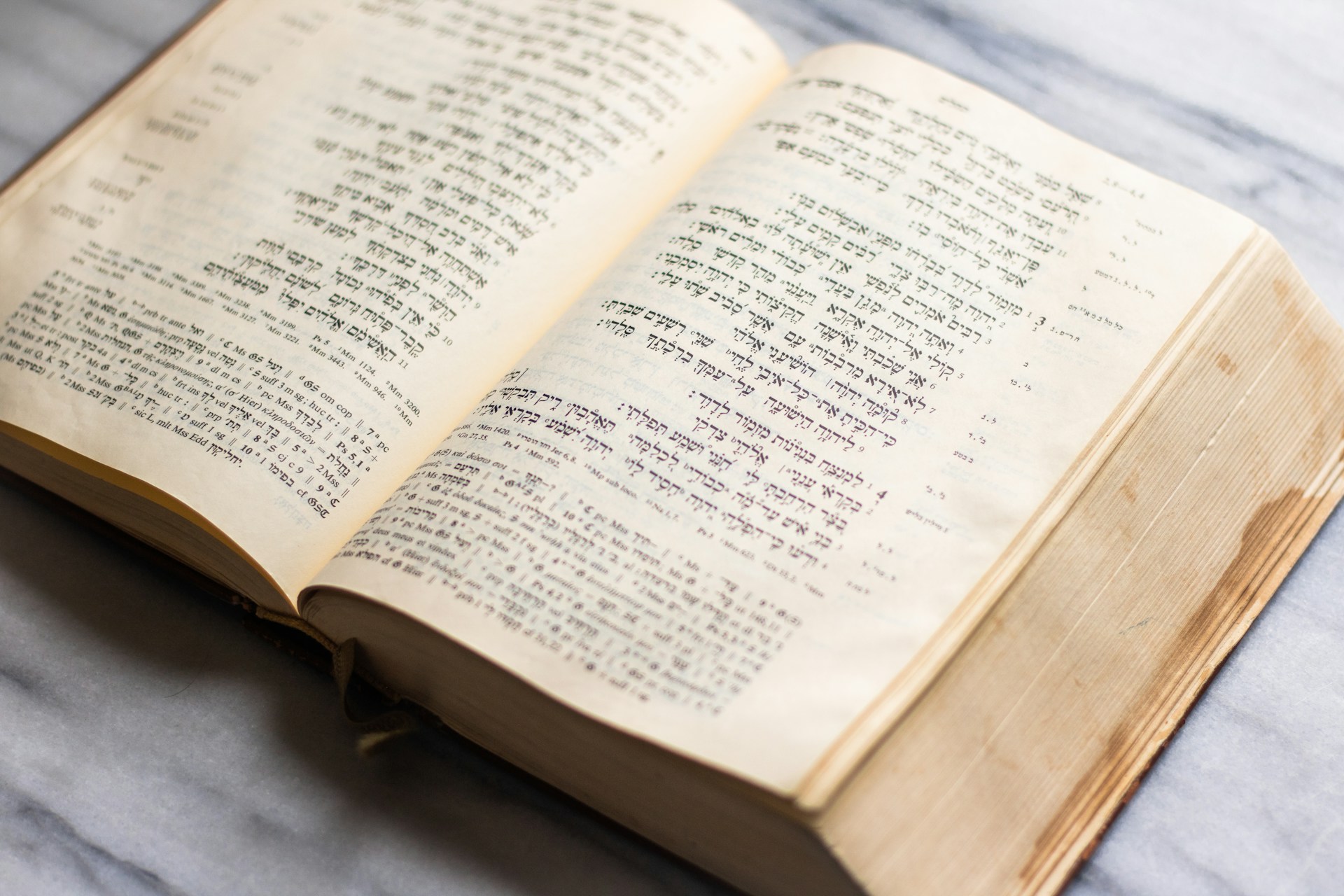

The original form of the text contained no vowels, but of course these were pronounced when the text was read. Many hundreds of years after the original text was written, that ancient oral tradition was added to the text—the dots and lines you’ve learned to interpret as vowel sounds, as well as the cantillation marks we talked about in the previous step.

Between 600 and 1000 c.e. schools consisting of families of Jewish scholars arose in Babylon, in Palestine, and notably at Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee to safeguard the consonantal text and to record—through diacritical notations added to the consonantal text—the vowels, liturgical cantillations, and other features of the text. Until these efforts such features had orally accompanied the text. These scholars are known as Masoretes or Massoretes, possibly from the (post-biblical) root msr ‘to hand down.’

—Bruce K. Waltke and Michael Patrick O’Connor, An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax (Winona Lake, IN:

Eisenbrauns, 1990), 21.

But they did more than adding markings: they made many detailed notes in the margins, and they tried to make their text as accurate as possible. Their different texts agreed in the vast majority of cases, but “[w]hen the traditions they inherited differed, they preserved the relatively few variants within the consonantal tradition by inserting one reading in the text, called Kethiv [meaning 'written'], and the other in the margin, called Qere [meaning ‘read’].”¹ Thus they kept the consonantal reading the same, since they didn’t want to alter the written text at all, but added “in the margin the form they considered correct.”²

Missing Vowels

So why are there no vowels under ולא in Psalm 100:3? When the UnfoldingWord Hebrew text prefers a ketiv reading, there are no oral tradition vowels to present since that tradition reads the qere aloud instead.

On Biblearc, a gold dot after the Hebrew verse indicates a ketiv/qere situation.

Click on the gold dot at the top of this step, and you’ll see both the original reading and the qere underneath.³

Why It Matters

Now you’ve seen that in Psalm 100:3, the qere reads וְל֣וֹ rather than ולא. Can you tell the difference? You wouldn’t be able to hear it, but the meaning of the two phrases is very different. The original consonants, ולא, say “and not,” so that the whole clause הֽוּא־עָ֭שָׂנוּ ולא אֲנַ֑חְנוּ would be translated, “he made us, and not we [ourselves],” as the KJV has it.

But וְל֣וֹ uses the lamed of possession, so that it would be translated, along with the 3ms pronominal suffix attached to it, “we [belong] to him.” The ESV follows the qere, and so translates the clause הֽוּא־עָ֭שָׂנוּ וְל֣וֹ אֲנַ֑חְנוּ as “it is he who made us, and we are his.” The ESV also has a textual note in its own gold dot, giving the ketiv reading.

So which reading is correct? That is debatable! The same reality holds for the rest of the ketiv/qere differences, and all other textual difficulties. God has so preserved his Word that, even in uncertainty about consonants and vowels, we can firmly know his revealed will and plan.