Lesson 3: The Contextual Horizon (1)

Using Rich Resources

Once you’ve chosen a good commentary, you can use it to discover the setting of a text—its historical context. So in this section, after defining “historical context,” we’ll look at six questions to ask of a text, and talk about two approaches to discovering historical context.

Definition

According to the reference site ThoughtCo,

[H]istorical context refers to the social, religious, economic, and political conditions that existed during a certain time and place.

Dr. Jason DeRouchie explains that when we are talking about studying the historical context of Scripture, our goal is:

to understand the nature and implications of the temporal, social, and physical situation in which the author wrote the text and to identify any historical-cultural-geographical details that the author mentions or assumes.

—Jason S. DeRouchie, How to Understand and Apply the Old Testament: Twelve Steps from Exegesis to Theology,

300.

We need to study historical context because, as Dr. DeRouchie reminds us, “[a]s God’s Word spoken through human words in history, every biblical book was conditioned by the language, culture, and situations of the time—some of which are like those of our age but a lot of which are not.”¹ Therefore, we need to identify “the shared assumptions between [the] author and audience” of a passage of Scripture we are studying—“elements that were clear to them but may not be as clear to us.”²

Six Questions to Discover the Setting

As you read Scripture, and as you turn to commentaries, what historical information should you look for? In other words, what questions should you ask of the text?

Dr. DeRouchie is extremely helpful here. He outlines six questions to guide your research.³

- Who? The authorship, audience, and major figures and powers of the passage.

- When? The original date of the message in relation to major periods and powers, including assessment of what events precede and follow…. (with consideration of potential influence either way).

- Where? The physical location and geography pointed to in the text.

- Why? The cause and purpose of the message.

- How? The genre and thought flow of the passage. At stake here is answering, “Why did he say it that way?”

- What? Here our focus is less on what is said and more on what is assumed in the text (e.g. worldview, social structures, customs, politics, religious practices, and geographic considerations).

Two Approaches to Take

There are two complementary approaches to discovering historical context.

Look for the historical context of an entire book.

This is important whether you’re studying a passage in detail, or wanting to master the content of an entire book. The book exists as a unit, written in a particular place and time; therefore, you should start by getting an overview of the historical context of the book as a whole.

To do this, first look at other books of the Bible to shed light on the situation of the book you are studying. For example, when studying Haggai, you should read Ezra 1–6 to fill out your knowledge of the events that Haggai’s audience had experienced and were living through when he preached his four sermons to them. When you are studying one of Paul’s epistles, you should investigate the book of Acts to find out more about what was happening in Paul’s life as he wrote, and the history of his relationship with the church or person he was writing to.

This is a critical first step because, as Dr. DeRouchie reminds us, “[O]ur knowledge of the ancient world is relatively small.”⁴ Therefore, “most of our wrestling with historical context must come from within Scripture itself and must be tested by the data found in the text. We must read, read, and reread the Bible.”⁵

But it may also help you, secondly, to explore a commentary afterward. One appropriate place is the introductory section of a commentary. Chances are there will be a section on the timing of the book’s writing, on what was happening in Israel’s world at that time, on the author, on the intended audience of the original writing, and more.

You should also step back a little further than this to locate where the book you’re studying is located within the story of redemption. (We’ll discuss this more fully in Lesson 6 with the Covenantal Horizon.) For example, Haggai preached during the postexilic period, after God had judged his people for their covenant unfaithfulness by scattering them from the Promised Land, and had brought them back in faithfulness to his covenant promises. Acts takes place after the culmination of God’s plan of redemption, Christ’s life, death, resurrection, when the ascended Christ is spreading the gospel to the nations through his apostles and growing his church. The events of every book of the Bible took place somewhere on the timeline of redemptive history, with part of the story already having taken place and other parts of the story still waiting to happen.

Look for the historical context of a specific passage.

On the other hand, if you are focusing on a specific passage, you can turn to the appropriate section in your commentary for more information on it. I’m not talking about looking for details about the grammar or logic or structure of the text, which will be the focus of Lesson 4. Rather, I’m talking about looking for specific historical or cultural information that will help you interpret a passage (see DeRouchie’s list of six questions above).

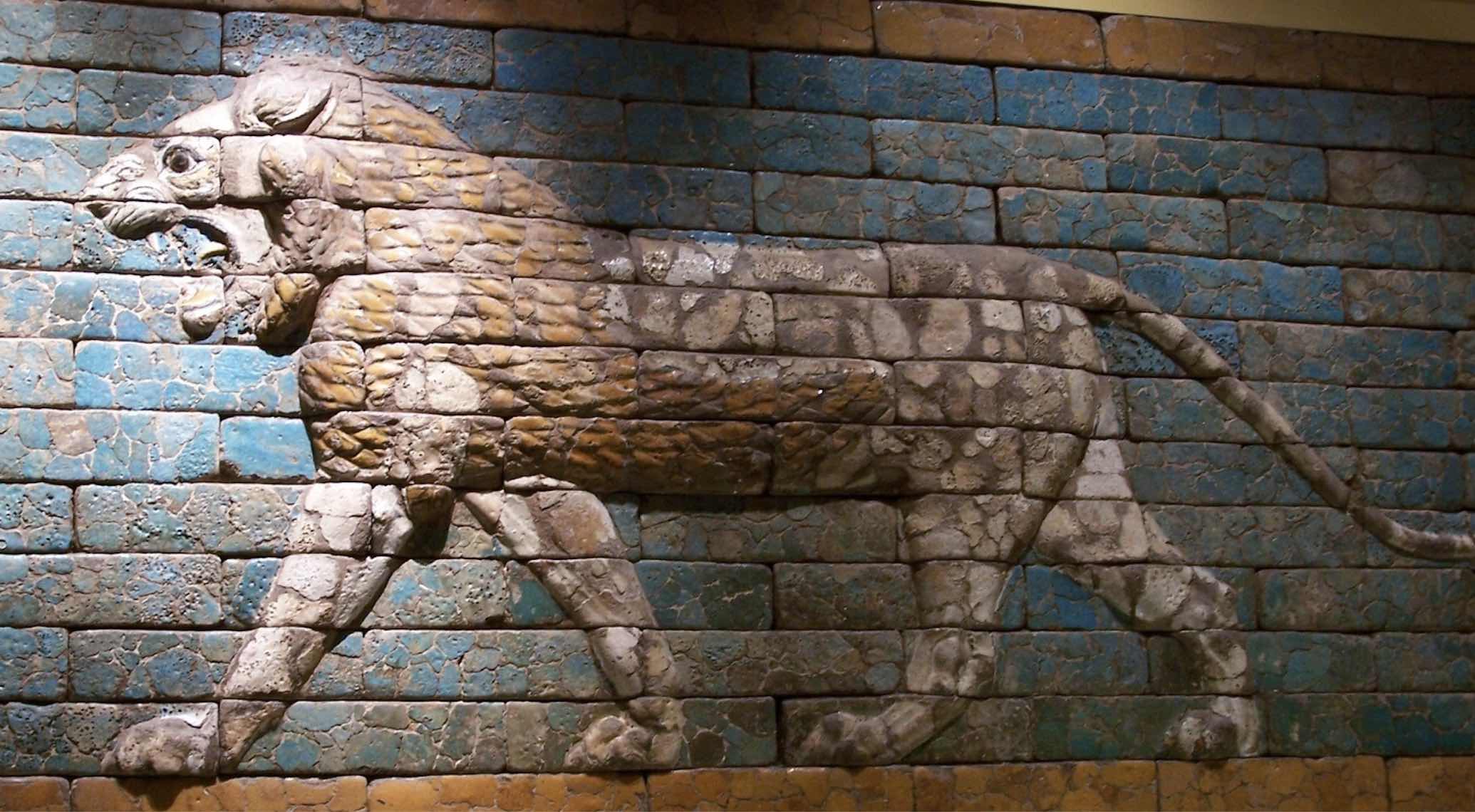

This is especially helpful in Old Testament narrative books that cover a long period of history like Genesis, Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles. It is also helpful when a passage contains an event or a reference that is culturally distant from us in the 21st century.

For example, the story of Ruth becomes more intelligible and fascinating when you understand the practices of pagan Moabites, the struggles of a widow in ancient Israel, and the practice of the kinsman redeemer. To correctly interpret what “cold,” “hot,” and “lukewarm” refer to in Revelation 3:15–16, you need to understand certain facts about Laodicea, Hierapolis, and Colossae. There are other references in the letters of Revelation 2–3, like the “white stone” of 2:17, that will be almost meaningless if you don’t understand their cultural significance.