Lesson 9: The Contemporary Horizon

Pickled Fish Theology

We backed and turned and wove our way out among the boats of the fishing fleet. In our rigging the streamers, the bunting, the serpentine still fluttered, and as the breakwater was cleared and the wind struck us, we seemed, to ourselves at least, a very brave and beautiful sight.

—John Steinbeck, The Log from the Sea of Cortez, 25.

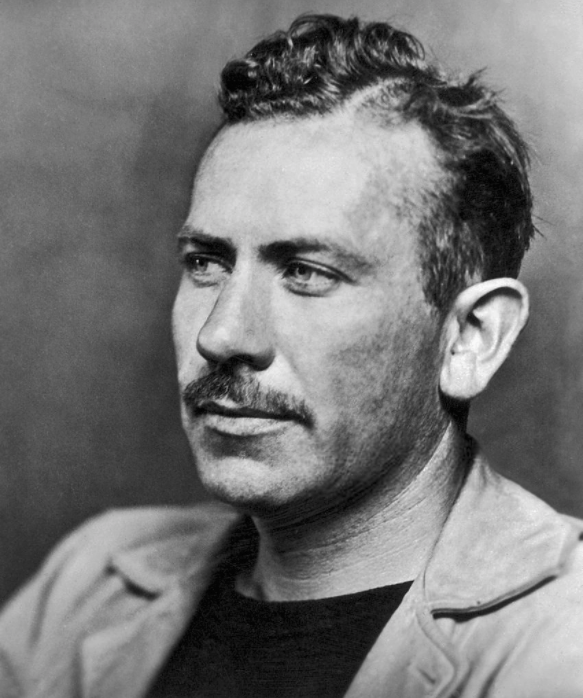

So launched the Western Flyer, with its crew, on a six-week specimen-collecting expedition along the coast of the Gulf of California in 1940.¹ The instigators of the trip were the famous novelist John Steinbeck and his best friend, biologist Ed Ricketts.

The two friends later collaborated on a record of their journey in a book, the narrative portion of which was published later under the title, The Log from the Sea of Cortez.² The book is unique—a combination of science, philosophy, and delightful story-telling, sometimes bland and sometimes hilarious.

The last half of the introduction to the book stopped me in my tracks and set my mind ablaze. Steinbeck explains that the reason for their trip was not merely scientific but was driven by a "wide and horizonless" curiosity.³ They didn't want to dispassionately record only "the external reality" of the fish, but also to experience the fish in its environment and so counterbalance scientific and experiential knowledge.⁴ Steinbeck describes this desired balance in his inimitable prose:

For example: the Mexican sierra has 'XVII–15–IX' spines in the dorsal fin. These can easily be counted. But if the sierra strikes hard on the line so that our hands are burned, if the fish sounds and nearly escapes and finally comes in over the rail, his colors pulsing and his tail beating the air, a whole new relational externality has come into being—an entity which is more than the sum of the fish plus the fisherman. The only way to count the spines of the sierra unaffected by this second relational reality is to sit in a laboratory, open an evil-smelling jar, remove a stiff colorless fish from formalin solution, count the spines, and write the truth 'D. XVII–15–IX.' There you have recorded a reality which cannot be assailed—probably the least important reality concerning either the fish or yourself.

—Ibid., 2, emphasis mine.

This is the way Bible students can slip into doing Bible study. If a "relational externality" exists between a fisherman and a fish, surely it exists between a seeker and God as well! If you are a human being, and if God is a personal being who created you, then there is a "relational reality" between him and you.

Ignoring that reality means that you will tell lies about your subject:

The man with his pickled fish has set down one truth and has recorded in his experience many lies. The fish is not that color, that texture, that dead, nor does he smell that way.

—Ibid.

God cannot be experienced by cold, fact-seeking, detail-recording, relationship-ignoring study. Yes, you can write down many true facts about God, like "God is an eternal spirit, existing in three persons, faithful, all-powerful, all-loving," but if you are not experiencing his triune presence, his faithfulness in trials, his power in difficulties, his love in sorrow, your experience is telling "many lies."

To avoid telling lies, Steinbeck and Ricketts established a goal. They would go on their expedition...

...so that in the end we could, if we wished, describe the sierra thus: 'D. XVII–15–IX; A. II–15–IX,' but also we could see the fish alive and swimming, feel it plunge against the lines, drag it threshing over the rail, and even finally eat it. And there is no reason why either approach should be inaccurate. Spine-count description need not suffer because another approach is also used.

—Ibid., 3, emphasis mine.

And studying theology "need not suffer"—indeed, will only truly benefit us—when our lives are being changed as we experience the God we study.