Lesson 1: Sola Scriptura

On Whose Authority?

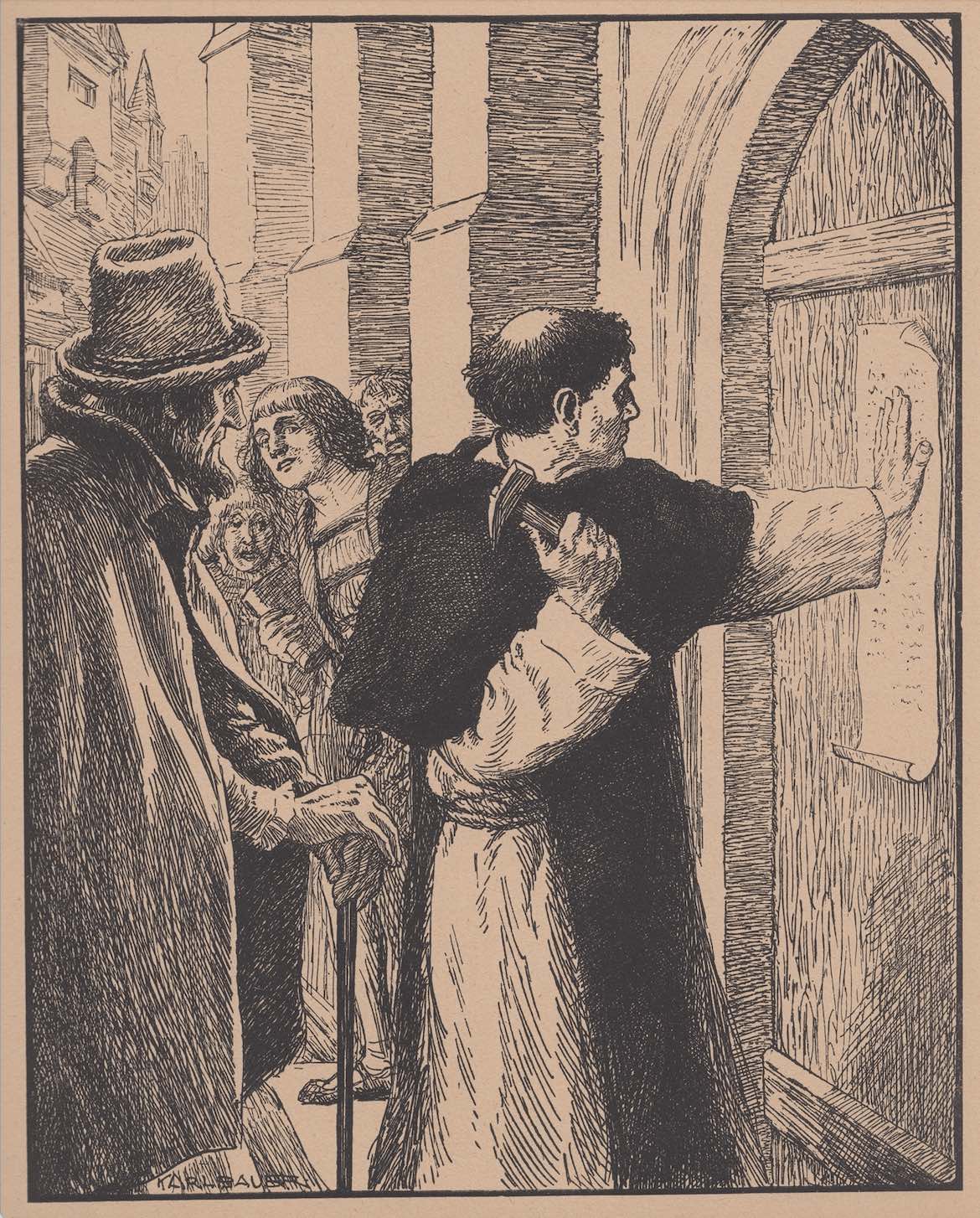

It is October 31. A Catholic monk marches down a street in Wittenberg, Germany, toward the Castle Church. He stops at the massive front doors, and spreads out a large sheet of paper on one of the doors. Then he pulls out a hammer and begins to nail the paper to the door—the custom when posting something you wanted people to notice, much like we staple garage sale posters to wooden light posts today. That paper contained 95 points, or “theses,” of concerns that the monk, Martin Luther, had with some of the teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church.

Now, this memorable picture is not quite historically accurate: it was probably someone else, like a janitor, who nailed the theses for Luther, and they may have been glued instead of nailed. But this scene is justly famous because it portrays the reality underneath what happened: Martin Luther boldly stood for truth against false teaching.

One false teaching that pervaded the darkness of 1517 was that the Catholic Church was the mother of the Bible. The Bible was the Church’s book, so the Church’s interpretation of it was the only correct one. The foundation for faith and practice was not the Bible alone—sola Scriptura—but was a combination of both the sacred Scriptures and the Church’s sacred tradition, (such as church councils and the Pope’s decrees), “two streams that form the one river of God’s Word.”¹

As the First Vatican Council would put it in the 19th century,

[A]ll those things are to be believed which are contained in the word of God as found in Scripture and tradition, and which are proposed by the Church as matters to be believed as divinely revealed.

The Catholic Church taught (and teaches), for instance, that the good works of Jesus Christ and holy believers of the past were stored up in a Treasury of Merit, and that the Pope could distribute this merit to whomever he wished to rescue them from Purgatory. The Bible says no such thing, but because the Church taught it, the faithful had to believe it as “the Word of God.”

These teachings filled the air like smoke that millions of people sucked in. They couldn’t breathe the clean air of the Scriptures, since the Catholic Church stood as a mediator between it and the common man. This mediator not only enforced its views as the only orthodox ones, but made sure no-one could discover any other views. They forbade individual access to the Bible by forbidding translations into modern language. The treasures of Scripture lay locked in dusty Latin.

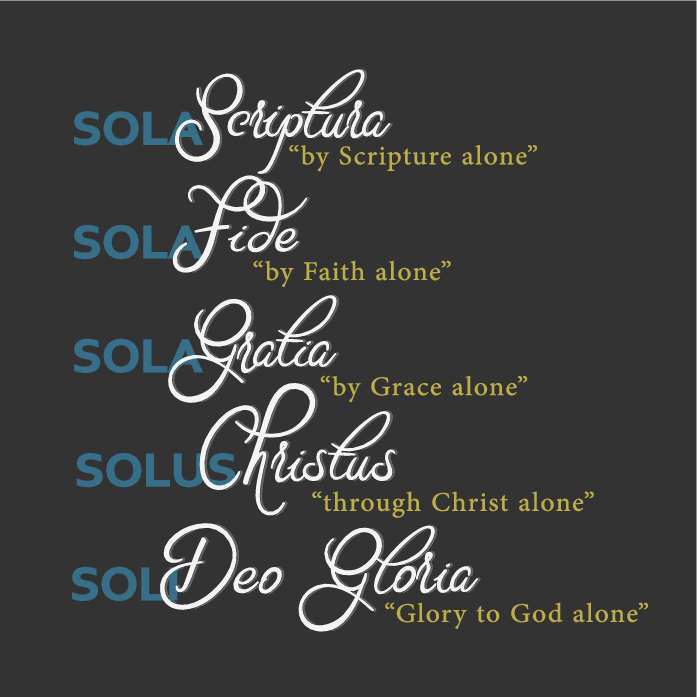

To battle against the lies and false doctrine of the Church, reformers like Martin Luther taught the truth of sola Scriptura. This was one of the “five solas,” which later historians have identified as five foundational rallying cries of the Protestant Reformation.

But when he began his fight against the corrupt teachings of the Catholic Church by making his 95 Theses public, Luther wasn’t trying to change the world. He didn’t know he was starting a globe-changing reformation! He was simply defending the truth of God’s Word. Yet his hammer did more than just nail the 95 Theses to a door. It cracked the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church in Europe so the light of the gospel could shine across that dark continent and into the rest of the world. As one of Luther’s biographers put it,

Luther was like a man climbing in the darkness a winding staircase in the steeple of an ancient cathedral. In the blackness he reached out to steady himself, and his hand laid hold of a rope. He was startled to hear the clanging of a bell.

—Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, 64.

And sola Scriptura—Scripture alone—was one of those five truths that rang out like bells in the decades following 1517. But what does “Scripture alone” mean?