Lesson 3: Learning Our Hermeneutic from the Bible

Example 3

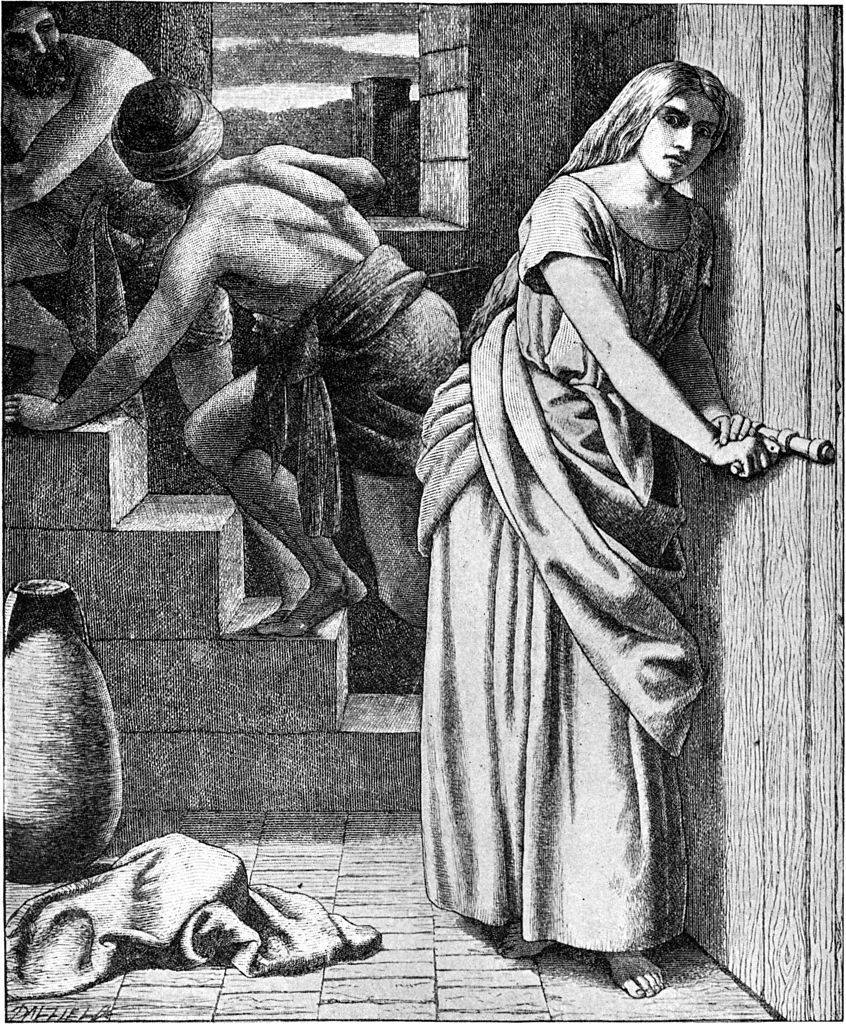

Our third case study considers how the author of Hebrews interprets the character of Rahab and the narrative surrounding her.

Rahab, a model of faith?

The author interprets Rahab, particularly her action to welcome the Israelite spies, as a model of faith. In doing so, the author is not twisting the narrative about Rahab to fit his point. Instead he follows interpretative principles established by earlier Scriptures. Thus, once again, we see an example of a biblical author following interpretative principles established by earlier biblical authors and expecting us to do the same.

By faith Rahab the prostitute did not perish with those who were disobedient, because she had given a friendly welcome to the spies. —Hebrews 11:31

The writer of Hebrews interprets Rahab’s actions as being “by faith.”

This is noteworthy because someone could very easily misinterpret Rahab as an evil person by noting her prostitution, her lying to and betrayal of her own people, and her motivation to save herself and her family. So what interpretive principles lead the writer of Hebrews to his conclusion about Rahab’s faith? By carefully reading Joshua 2 and 6, we can see that the author of Hebrews is following interpretive principles established by the Bible itself.

For example, the Bible teaches us to interpret a person’s character based on the combination of their confession, actions, and the outcome of their life.

We see this principle in the book of Job. This book (not to mention elsewhere) teaches us that we cannot condemn a character in biblical narrative for unknown sin simply due to hardships in their lives. We also see this principle in the stories of Balaam and King Saul, who show us that confession at one point in life does not mean much. Yet, the combination of a consistent confession, faith-filled actions, and a positive outcome give weight to the authenticity of the person’s heart. We find this with Rahab. She had a clear confession of why she was doing what she was doing, and it was focused entirely on the Lord. (Josh 2:8–13). Her actions matched this confession (Josh 2:4–6, 15, 21). And she was blessed for the long-term (Josh 6:25; Matt 1:5).

Another example involves how the author of Hebrews follows Joshua‘s lead by focusing on Rahab. We might not naturally think of Rahab as a significant character. Perhaps it surprises us that Hebrews 11 mentions her. But the author of Hebrews is merely following the author of Joshua. The book of Joshua itself slows down the narrative to highlight Rahab. The story in Joshua could have mentioned her help to the spies and passed by, but instead it lingers with her—and then comes back and follows up with her. When a biblical narrative highlights a particular character, it is never without significance. The author of Hebrews demonstrates this interpretative principle by paying attention to the characters emphasized by Scripture itself.

Finally, the author of Hebrews follows Joshua’s lead in another way. He follows the logic in the text and expects us to do the same.

Joshua 6:25 (as well as Joshua 2) clearly indicates that Rahab was saved because of her help to the spies. The writer of Hebrews does not just echo details of Rahab’s story, but the clear logic in the text as well. He cites her help to the spies as the reason she “did not perish.”

In lessons 5 and 8, we will explore interpretive principles related to specific genres like narrative and prophecy. For now, note once more that the author of Hebrews teaches us that faithful biblical interpretation follows the Bible’s own principles and practice, and he expects us to understand and follow his interpretation of Rahab.